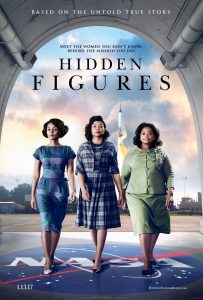

As many of you might know, Hidden Figures (2016) is a biopic directed by Theodore Melfi based on Margot Lee Shetterly’s popular history book and New York Times Bestseller, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race (2016). The film about the NASA’s black female computing group at Langley’s Research Center during the Space Race was nominated for three Oscars and has reaped high praise from movie critics the world over. I was among the droves of people who rushed to the theater to see the movie when I read that Hidden Figures is an inspirational film that makes little known achievements of intelligent, determined women visible. I also appreciated the fact that this ‘feel good’ Christmas film might encourage girls to seek Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) careers. The plot also avoided all too familiar themes in black films, such as brutal beatings and rape of black women, which were taken to an extreme in Precious and 12 Year’s a Slave. It seemed like a win-win situation for all and the perfect story of triumph in dark times. And to be honest, that is exactly how I experienced the film. Well, at first. Then I read the book.

Before I get to my criticism of the film, I want to make it clear that I still value the motion picture Hidden Figures and find the cast and especially the acting talents of Octavia Spencer, Janelle Monáe, and Taraji P. Henson in the respective roles of Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, and Katherine Johnson remarkable. The film brings both important and lesser-depicted themes, e.g. the rapport and friendship between black women, to the big screen. While Hidden Figures remains a good film overall, it misses the mark in a few important areas.

After reading the book on which the film was based, I was disappointed that the motion picture avoided a serious discussion on structural discrimination. Katherine Johnson was the only character to be shown prior to her work at NASA as a black female mathematician, and the shot chosen reflected her love and talent for mathematics as a child. Nothing wrong with that, but by only concentrating on this one flashback, the film misses an opportunity to put the accomplishments of the other characters and the challenges they faced into a larger context.

Before working at Langley, all three of the actual black calculators were so poorly paid as teachers that they needed to supplement their salaries during the summer months. Dorothy Vaughan and her husband, who also had seasonal jobs as a bellman at luxury hotels, wished to provide a better life for their children. So Dorothy Vaughan, for example, took up a menial summer job as a laundry worker for the military at Camp Pickett in 1943. Even after Vaughan, a mother of six, eventually landed a job at West Computing earning about $2,000 per month, Shetterly reports that Vaughan would often take “a walk around the block until the children were done eating. Only then would she serve herself leftovers.” Vaughan knew what sacrifice meant, and to put her wages in context, the average monthly wage for black women was only $96 during the 1940s. This is, indeed, a hidden figure.

Additionally, Katherine Johnson’s multiple trips – rain or shine – to a ‘colored’ bathroom across the NASA campus shown in the film are certainly a non-threatening way to bring the topic of segregation to new generations. The scenes set to light-hearted music and the click-clack of Katherine’s high heels, however, undermine the ugly humiliation of structural discrimination and its detrimental effects on body, mind, and spirit. Johnson silently endures her long trips to the bathroom as well as a ‘colored’ coffee pot forced upon her until her boss, Al Harrison (Kevin Costner), confronts her about her ‘disappearing act.’ The audience cheers Johnson on as she gives her impassioned speech about the indignities she has had to endure. Yet the powerful scene is somewhat undercut shortly thereafter. Mr. Harrison becomes the ‘white savior’ figure, ridding the department of the coffee pot and beating down the ‘colored’ sign in front of the ‘colored’ bathroom until it is shattered to pieces.

In real life, Johnson refused to use ‘colored’ bathrooms, and apparently nobody confronted her when she frequented the ladies’ room closest to her work place. Likewise, already at the beginning of the 1940s, Miriam Mann, a employee at West Computing – who was not depicted in the film – actively fought against segregation. One day, Mann began to remove the ‘colored’ sign on West Computing’s table in the cafeteria, even after a new one continued to replace it day after day. At the risk of losing her job, Mann insistently continued the fight until one day the ‘colored’ sign mysteriously disappeared forever. She did not need a supervisor to do that for her. And yes, Dorothy Vaughan did have to wait two years to become supervisor of her section, but this achievement was already made in 1951, over a decade earlier than is shown in the film. These are just a few examples found in Shetterly’s book, but they reveal the film’s missed opportunities to show vital areas of real contestation by black female mathematicians at the cost of conjuring up or exaggerating conflict in a non-threatening, entertaining drama.

Finally, as many history-oriented films do – according to Rosenstone’s article, “The Historical Film: Looking at the Past in a Postliterate Age” – the solution of the main characters’ personal problems might misleadingly seem like solutions to general historical problems. A Hollywood-style happy ending leaves viewers uplifted, but – at the same time – it fosters neither agency nor critical insight. Having sided with the three leading characters, the audience might just leave the theater thinking that they have done their part by feeling empathy with Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, and Katherine Johnson and leave it at that.

Just as African American history month celebrates the neglected accomplishments of black Americans, the film Hidden Figures does as well. However, after reading the book, the word “hidden” in the film’s title takes on an entirely new meaning.

16,863 Total Views, 2 Views Today