Our first contribution, “New Kids on the Blog,” was uploaded on September 8, 2014. We were excited to try our hands at blog writing, something none of us had ever done before, at least not on a regular basis. Used to writing academic papers, books, or book chapters, we at first found the new medium too cursory and maybe also too frivolous, in short: not academic enough. But we soon discovered that “short” does not necessarily mean “not serious” or “too superficial.” So slowly but surely, we learned to love the short form, spiced up with images, video clips, podcasts, and movie trailers. Soon, we started recruiting writers from across the globe, inviting them to share their views on U.S. history, politics, arts, and the media. Some of the contributions were critical of U.S. politics, but most celebrated the U.S. for its creative energy, its innovative strength, and its ability to constantly rejuvenate.

Occasionally, our blog assistants would try their hand at blog writing. In the last few years, we couldn’t help but notice the generational differences between us and our blog helpers and the interests close to their hearts. Consequently, blogs started to focus on fantasy films, digital distractions, and non-binary and transgender identities.

One of the highlights for us was recruiting and/or interviewing award-winning authors such as Charlene L. Edge, Saloma Miller Furlong, Michael Lederer, Jayne Ann Philipps, Andrew Ridker, Drew Hayden Taylor, and Ira Wagler.

Overall, we published close to 400 blogs, which attracted readers from altogether 184 different countries! Our most faithful readership came from such diverse countries as the U.S., followed by Germany, China, France, the Russian Federation, Canada, and the Ukraine.

As one of our final tasks, we are currently preparing the American Studies Blog data for inclusion in the Leuphana Digital Archive. After the process has been completed, the American Studies Blog will continue to be available to researchers and a wider public long after the current website disappears.

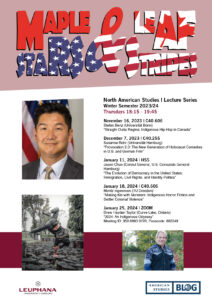

Although the ASB was one significant and vital constituent in American Studies at Leuphana, North American Studies will continue with both the NAS profile in Complementary Studies and our lecture series, “Maple Leaf & Stars and Stripes.” For talks during the coming fall semester, please check out the poster:

Finally, our blog wouldn’t have been such a success without our faithful contributors and readers. Additionally, we’d like to thank the United States Embassy in Berlin for their generous funding. Last but not least, we dedicate this final blog to Dr. Martina Kohl for her unwavering support.

We had 9 great years and hope you did, too!