On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Martin Luther King Jr. touched thousands of people with his unforgettable “I have a Dream” speech on August 28, 1963. In the face of discrimination against African Americans, more than 250.000 activists protested during the famous March on Washington. That very same day, in the very same place, another watershed moment occurred: The New York folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary sang a cover of “Blowin in the Wind”, forever adding Bob Dylan’s masterpiece to the canon of American protest music.

Of course, the notion of protest music existed long before the 1960s: Enslaved African Americans laboring on plantations used spirituals to sing about the horrors of slavery, likening their suffering to the plight of the exodus of the Hebrews. More than a hundred years before the Civil Rights movement, music was used as a covert confrontation of institutional slavery and systemic racism.

Even decades after the abolition of slavery in 1865, injustice continued during the first half of the twentieth century. Jazz legend Billie Holiday picked up on that notion and recorded the chilling protest song, “Strange Fruit”. Based on a poem by Abel Meerepol, the song attacks the atrocious lynching of black boys and men in the South. The horrors came to a head in 1955 Mississippi, when 14-year-old Emmett Till was gruesomely murdered for allegedly whistling at a white woman.

The same year, in Minnesota, a different 14-year-old named Robert Allen Zimmerman did not know yet that this horrendous story of the boy’s murder – who could have been his peer – would strike a chord in him. Nor did he know that one day, by a different name, he would write one of his first protest ballads in the name of Emmett.

It is this commitment to the cause that would shape the 1960s in terms of music, politics, and civic action. In 1961, the very same Robert Allen Zimmermann – who called himself Bob Dylan by now – moved from Minnesota to New York to pursue his interest in folk music. During this time, Dylan’s beliefs were stirred by the Talmudic tenet that those who can fight injustice and do not are accomplices to it. Dylan understood that his moral responsibility was to use his voice against the brutal injustices African Americans had been subjected to for centuries.

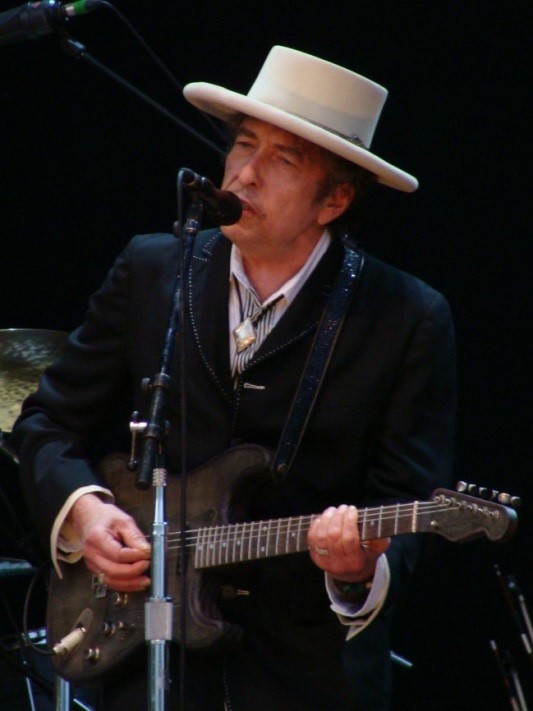

The revelation came in 1962 when the 21-year-old read the autobiography of one of his great heroes, acclaimed folk singer Woody Guthrie. His attention was immediately drawn to a line in which Guthrie likened his political views to newspapers blowing in the wind on the streets of New York. Legend has it that “Blowin’ in the Wind” was written within ten minutes in a coffeehouse in the Village and performed the very same day. Indeed, it is the simplicity of those three verses that would make it a hallmark of folk music and catalyze Dylan’s musical career to the point of winning the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. But what is it about this simple song that would become a cultural and musical icon?

The themes of “Blowin’ in the Wind” are broader than the Civil Rights movement since the promotion of freedom, peace, and moral responsibility goes far beyond the 1960s. It is these universally human sentiments that have caused the song to be covered over and over again – for instance by Sam Cooke, Joan Baez, and Johnny Cash.

Yet there is something else that has caused this song to prevail: It has the power to reassure those who suffer from discrimination, to mobilize those who can and want to fight it – and to unsettle those who perpetuate it. It’s no coincidence that Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in the politically turbulent year 2016. To this day, his questions remain as relevant as ever.

20,711 Total Views, 2 Views Today