Newspapers always make good movies: the dare-devil reporter, the overachieving assistant, and the crusty editor up against the power of a dishonest government. There is wonderful symbolism in the heavy lead type spelling out a scandal and the broad sheets of newsprint rolling off the presses to cover the nation. The audience is assured that the truth will come out.

Newspapers always make good movies: the dare-devil reporter, the overachieving assistant, and the crusty editor up against the power of a dishonest government. There is wonderful symbolism in the heavy lead type spelling out a scandal and the broad sheets of newsprint rolling off the presses to cover the nation. The audience is assured that the truth will come out.

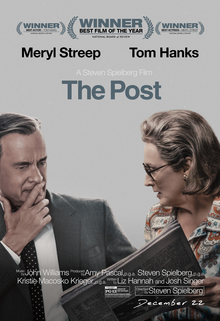

The publication of the Pentagon Papers is a perfect crusading newspaper story. It starts with the intellectual, once hawkish, Marine veteran stealing and photocopying secret papers and giving them to The New York Times for publication, revealing 30 years of the government misleading the populace about the Vietnam War. The Post, directed by Steven Spielberg, begins in Chapter 2, with editor Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks) frustrated and embarrassed by having been scooped, once again, by The Times. When the government gets an injunction, barring The Times from further publication, The Post, in the words of Bradlee, is “in the game.”

It isn’t the only game The Post is playing, however. The company is cash poor and generating little profit. In order to raise the capital they need for vital improvements, publisher Katherine Graham (Meryl Streep) and her advisors decide to offer stock to the public. She is told that some potential investors are reluctant because a woman is in charge. If the Pentagon Papers are published, the risk might heighten; the stock price might be depressed; and in a worst-case scenario, the sale might be cancelled. The government is threatening to sue. Graham and Bradlee could be indicted; assets are possibly in peril; and the future of the company is hanging in the balance. The fact that these highly risky opportunities come at the same time makes for good drama and fascinating history.

Graham has grown up with The Post and understands the news business well. Her father left the paper to her husband Phil, who had everyone’s respect as a brilliant publisher. Katherine didn’t object; that was the way things were done in those days. She was, more than anything, a socialite, a role she did not surrender when she took over the paper after Phil’s suicide. She felt confident in her office off the news room, but much less so in the board room, where she was the only woman sitting with 21 men who did not give her the respect and attention a publisher might expect to get. Nevertheless, the existential decision of whether to run the story would ultimately be Graham’s, “a woman,” Streep said in an interview, “who didn’t think she belonged in her job.”

This is history – not a documentary – so we know how it ends. Some details are changed, and the time line is adjusted for a better flow. Yet, the movie does not take the usual liberties with the facts that Hollywood is infamous for. It looks and sounds and is much like it really was, and it was a different time; perhaps – in the world of news – a better time. It brings us back to a day when Americans got the news from newspapers, printed by a heavy lead alloy on broad sheets. Twentieth century American newspapers told the truth, not invariably, but consistently enough that we believed what we read. We didn’t talk of ‘fake news’ or ‘alternative facts’.

It also brings us to that time when women learned that they can demand respect. Katherine Graham was born to power, but it took courage for her to claim that birthright.

If you are interested in the historical figure on Graham, here’s an excellent article on her struggle to the top of the ladder.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrXlY6gzTTM

20,070 Total Views, 5 Views Today