In 2011, Saloma Miller Furlong’s Why I Left the Amish: A Memoir appeared during the memoir boom that gave agency to invisible, marginalized, or misrepresented groups. Why I Left the Amish was one of the first memoirs written by a former Amish woman that provided unfettered perspectives on the Amish. While many Amish groups today lead a simple life much like many rural Americans in agricultural communities did in the 19th to early 20th centuries, Amish culture is anything but simple as Furlong’s newest memoir shows.

In 2011, Saloma Miller Furlong’s Why I Left the Amish: A Memoir appeared during the memoir boom that gave agency to invisible, marginalized, or misrepresented groups. Why I Left the Amish was one of the first memoirs written by a former Amish woman that provided unfettered perspectives on the Amish. While many Amish groups today lead a simple life much like many rural Americans in agricultural communities did in the 19th to early 20th centuries, Amish culture is anything but simple as Furlong’s newest memoir shows.

In her inaugural memoir, Furlong chronicles the life of a young Amish girl and teen who grows up in an insular Amish community in Ohio, struggling to fit in and make sense of the Amish faith and its rules. At the same time, Furlong reveals a web of physical, mental, and spiritual abuse committed mostly by Amish males and the inability of the Amish culture to deal with it. This is certainly not the kind of story perpetuated by Amish romance novels so many people around the world like to read. Yet, the book has sold over 12,500 copies and reached many readers in public libraries and an unknown number of practicing Amish people.

Through her socialization in a patriarchal society, it seems logical that Furlong placed much of the blame for her pain and trauma in Why I Left the Amish on the male figures who abused her and the Amish minister of her community who enabled the abuse to continue. Yet the unwillingness of her mother to admit her role and engage in a reconciliation process with Furlong led the memoirist to embrace new perspectives. After taking another hard look at her life, Furlong ultimately concluded that her mother was anything but a powerless victim limited by her roles as a woman and mother in Amish culture.

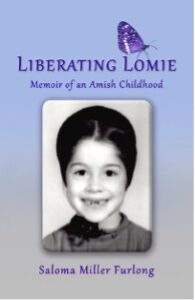

In her third memoir, Liberating Lomie, Furlong revisits her childhood memories from the vantage of a mother-daughter relationship. And that bond, like Amish culture, is complicated.

Liberating Lomie is told in chronological order, beginning with the tender stories of a nurturing mother who cares for her baby. In a communal society in which submission is deeply embedded in the culture, individuality is frowned upon. Amish culture teaches that a child’s will must be broken, and Furlong’s mother embraces that obligation to excess. The adversity begins when Lomie, Furlong’s Amish name, begins to both question her mother’s directions and develop a will of her own. In between glimpses of happy childhood memories as the third of seven children, Furlong recounts daily drudgery of endless housework, personal disappointment, a variety of physical punishments and beatings, incidents of sexual molestation, and the uninspired fulfilling of religious expectations. When Mem, Furlong’s mother, refuses help twice from a social worker, Furlong hits rock bottom. She decides to either take her own life or run away.

Stories about mothers and daughters have been circulating in society for as long as humans have existed. Liberating Lomie, however, breaks new ground. It takes a hard look at Amish womanhood and describes the multifaceted harm that breaking a child’s will can do. A number of the chapters in Liberating Lomie will be familiar to readers of Why I Left the Amish, most of them reframed. Others, such as “Ponce de Day Leon,” which won the award for best non-fiction at the 2018 Tucson Festival of Books, are new. Writing against the grain takes courage, and Furlong masters that challenge with brilliance.

11,052 Total Views, 2 Views Today