Is it okay to dog-ear or write in your books? This question remains a heated topic among readers. I always thought it was stupid to care what others did with their books but preferred to leave mine in their original state.

Is it okay to dog-ear or write in your books? This question remains a heated topic among readers. I always thought it was stupid to care what others did with their books but preferred to leave mine in their original state.

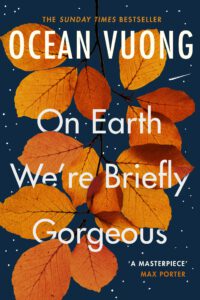

This all changed for me when I started reading Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Vuong’s words were so beautifully constructed that simply reading them didn’t feel enough. I wanted to force myself to linger. I wanted to embrace the parts that had touched me, wanted to firmly secure the passages I’d later return to.

Or, less dramatically, I wanted to mark my book.

And I wanted to do it with an orange pen, one that would match the cover’s autumn leaves. Ever since acquiring said pen, I haven’t stopped talking about the writing.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous consists of a letter written by Little Dog, the protagonist. It’s addressed to his illiterate mother. Therefore, a letter’s typical purpose, reaching the recipient, is doomed to fail from the start. At its core, it’s a story about language – and its limitations. I believe the best way to introduce the book’s plot is less by describing it and more by showcasing Vuong’s words instead. Yes, that means there are minor (!) spoilers ahead.

- Little Dog is Vietnamese American, his family had to flee the Vietnam War. From then on, it was Little Dog’s job to learn English and communicate for his mother. Mastering the language necessary for survival: “I am writing because they told me to never start a sentence with because. But I wasn’t trying to make a sentence – I was trying to break free. Because freedom, as I am told, is nothing but the distance between the hunter and its prey.”

- Little Dog’s mother started hitting him at the age of four. At some point, years later, she says out of nowhere: “I am not a monster. I’m a mother.” Little Dog replies: “You’re not a monster.” He then goes on to say: “But I lied. What I really wanted to say was that a monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin word monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.”

- Another important subject is mental health, especially as it relates to addiction. “It’s the chemicals in our brains, they say. I got the wrong chemicals, Ma. Or rather, I don’t get enough of one or the other. They have a pill for it. They have an industry. They make millions. Did you know people get rich off of sadness? I want to meet the millionaire of American sadness. I want to look him in the eye, shake his hand, and say, ‘it’s been an honor to serve my country.’”

- Little Dog falls in love with Trevor, a guy he meets at work. Including a passage from the book would not be possible spoiler-free, but here’s how Vuong describes their relationship in interviews: “From a queer perspective, queer people understand that failure is the beginning of their identity. They fail to fit in. They see failure as the first stage in a culture that sees failure as the last and final gravestone to a project. This is two people trying to find pleasure for each other in a world that would prefer that they vanish.”

- To round up the quotes, here’s the passage that inspired the book’s title: “I am thinking of beauty again, how some things are hunted because we have deemed them beautiful. If, relative to the history of the planet, an individual life is so short, a blink of an eye, then to be gorgeous, even from the day you’re born to the day you die, is to be gorgeous only briefly. The sunset, like survival, exists only on the verge of its own disappearing. To be gorgeous, you must first be seen, but to be seen allows you to be hunted.”

These snippets don’t do justice to the book in its entirety; nonetheless, I hope they provided a little insight of what to expect. Enjoy the read, and I’ll leave you with Ocean Vuong’s recitation of his poem, “Nothing.”

2,255 Total Views, 7 Views Today