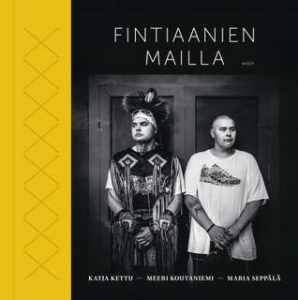

In their 2016 book, Fintiaanien Mailla, three Finnish women take readers on a journey into unknown territory. Meeri Koutaniemi (photo journalist), Maria Seppälä (journalist and documentary filmmaker), and Katja Kettu (bestselling author) introduce us to Findians, a group of people who practically nobody has heard of, at least until now.

In their 2016 book, Fintiaanien Mailla, three Finnish women take readers on a journey into unknown territory. Meeri Koutaniemi (photo journalist), Maria Seppälä (journalist and documentary filmmaker), and Katja Kettu (bestselling author) introduce us to Findians, a group of people who practically nobody has heard of, at least until now.

Between 1860 and 1940, approximately 400,000 Finnish emigrants left their homeland for North America in search of a better life. They mainly settled in Minnesota, Michigan, and Ontario. 400,000 is an amazingly high number, especially when one considers that Finland only had a population of about three million people in 1900. In their new homeland, the Finnish came in contact with the Ojibwa people. Relatively quickly, the indigenous people and the Finns noticed that they had much in common:

• A deep respect for nature, in particular their appreciation of the forest

• A belief that poverty is a result of a limited education

• A long tradition of sweat lodges

• Prejudices of mainstream society against the marginalized

Due to these shared factors, the fear of first contact was significantly lower between these two societies than it was when Native peoples first met other European settlers. The Ojibwas and Finns worked together in forestry and fishing, lived together, and became friends. Some fell in love, had children and a new ethnic group was born: The Findians.

Yet, they still have not been formally recognized. Similar to the Métis – descendants of European trappers and fur traders and women including the Cree and Ojibwa in Canada who have been recognized as indigenous people in Canada since 1982 – Findians are still campaigning for this status.

Thanks to the three authors, we finally get to know the Findians. Meeri Koutaniemi’s impressive black and white photos show strong, determined individuals. Supplemented by texts and interviews by Maria Seppälä and Katja Kettu, this thought-provoking book provides an overall picture of the current life of the Findians in which much of the Finnish language and culture has been preserved. In addition, it documents how their struggle for recognition is still shaped by poverty and exclusion. Hopefully, this book by the three Finns will help support the Findians in their fight for recognition. At the very least, a translation of this important book into English would be an important step to help them gain the recognition they deserve.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmNv-piZOmo

I’d like to leave you with one small piece of trivia. An important descendant of the first Finnish immigrants is the American politician John Morton (1725–1777), who signed the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 for Pennsylvania. Now you can hardly get more American than that!

33,578 Total Views, 6 Views Today