Everyone reading this blog has seen monuments to historical events or national heroes. But how many of you have seen a memorial to a mass hanging? Outside the movies or TV, few people today have ever seen a public hanging. That was not true a hundred years ago when criminals’ lives often ended at the end of a noose. The largest public hanging in American history took place on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota. That day, federal troops executed 38 Dakota Sioux Indians for their part in the Minnesota Sioux War that had just ended. By some accounts, up to 4,000 whites jammed the town square or sat atop nearby buildings to watch the mass execution. The crowd cheered loudly when the trapdoors opened and all 38 men hung at the end of the ropes. Why not take a few minutes to find out why this gruesome spectacle happened 134 years ago and how the city of Mankato – often associated with the Little House on the Prairie TV series – has dealt with this legacy?

This mass hanging came at the end of a short, bitter war between the Dakota Sioux who lived along the Minnesota River and crowds of nearby settlers. The intruding whites had settled land near the two Indian agencies limiting the Dakota’s ability to hunt the deer they needed for food. As a result, some of them accepted American demands that they become farmers, leaving more land available for the whites. They received food and other necessities from the local Indian agent, and their neighbors assumed they posed no threat. It came as a terrible shock in August 1862 when bands of Dakota men attacked the settlers, setting off a war and killing nearly 800 whites. When the fighting ended, U.S. forces held 1,500 Indian captives, and a military commission tried many of the men for murder, rape, and robbery. At the trials, 303 of the men were sentenced to death. After reviewing the proceedings, President Abraham Lincoln pardoned all but 38 of them.

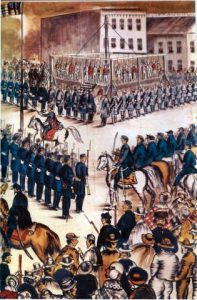

Scheduled for December 26, 1862, the hangings took place on a specially built large square gallows that would allow all of the men to be executed at the same time. Infuriated white spectators had threatened to kill all of the captive Sioux, not just those to be hanged, so hundreds of troops stood guard to prevent violence. Once all of the prisoners had died, authorities removed their corpses and buried them in a shallow grave. Because of the high demand to get cadavers for anatomical studies, local doctors opened the grave that night and removed all of the corpses.

Local interest in the mass execution faded, and the event dropped out of public discussion until 50 years later. As early as 1902, the Mankato newspaper mentioned that people had offered to raise funds for a memorial to the event, and in 1911, two men who had been in the war formed a committee to locate the site of the hangings. Their efforts led to public support for erecting a memorial to the event on the site it had occurred.

Almost from the start, people questioned having a public memorial to such a grisly event, but its supporters claimed that it honored the memory of the pioneers who died in the conflict. By 1922, objections to the marker led to public discussion calling for someone to remove the monument. Lorin Cray, leader of the effort to build the monument, defended it saying that “the hanging of those Indians was an act of justice … and it should not be forgotten.” His opponents countered that “the execution of the Indians is not the sort of thing to which Americans erect monuments.” Meanwhile, the marker had to be moved in 1942 and again in 1965, so that it no longer stood on the spot of the hangings. By 1971, the social revolution that swept through American society brought the matter to a head, and authorities removed the existing monument. A few local leaders worked with the Minnesota and the Blue Earth County Historical societies to begin creating a new memorial “acceptable to both Indian and white.”

In 1977, they erected a modest-sized plaque at the county library. Ten years later, the City of Mankato declared a Year of Reconciliation and began an education day for all third grade children to learn about Dakota customs. In 1992, the city bought the hanging site, established Reconciliation Park, and placed the statue of a large white buffalo there. Twenty years later in 2012, they erected a memorial that looked like a large buckskin engraved with the names of the men who died there.

Each year, Dakota tribe members hold a run from Ft. Snelling in Minneapolis to Mankato as their way of marking the event. As part of activities relating to the hangings, Mankato hosts an annual Powwow celebration to bring whites and Indians together. Today, through its reconciliation efforts, the city has replaced nearly all signs of the 1862 hangings and has erased public references to the worst public execution in American history.

A Minnesota art exhibit also marked the 150 anniversary of the mass hanging.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fifVfoarhMU

22,478 Total Views, 6 Views Today