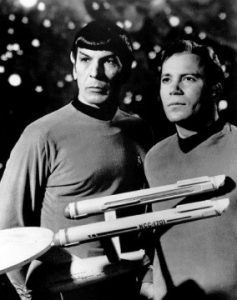

Okay, I am going to have to out myself here seeing that it’s the 50th anniversary. I am a trekkie! I grew up with Captain Kirk, Spock, and Lt. Uhura. The crew and adventures of Star Trek are to blame for my lifelong interest in science fiction. Well, the moon landing is also up there on my list. Why science fiction, you ask?

For me, the trip into the unknown future is always a journey into the psyche of the zeitgeist. What was the world like then, and what did people fear, adore, or hope for? That is sci-fi for me. Take Star Trek. Looking at the original sixties series from today’s perspective makes it seem antiquated and quaint, but it was cutting edge back then. A Russian on the bridge together with an American? A Black woman on the bridge? The Cold War was cooling down, but animosity was still running high. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had just been passed when Gene Roddenberry wrote a sci-fi TV series which, after some changes, eventually ended up as Star Trek, first airing in 1966. Definitely, this program pushed the envelope of social progress with one of the first interracial kisses on TV.

Star Trek is also about science and how technology influences society. For example, everyone takes sliding doors for granted. However, it wasn’t until Star Trek that they were invented and then used. A coincidence you say? After all, it was only a story. What else did Star Trek come up with? Cell phones — that is why some of the first ones opened up just like the ‘communicator’ in Star Trek. Then you have PCs, tablets, large screens, wireless ear pieces, and portable storage devices. There is still some debate as to whether the replicator, or food synthesizer as it was called in the original series, is actually in use today. Let’s face it: science fiction changes society.

But what about the academic perspective? According to the late Carl Sagan, former Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences at Cornell University, science fiction is like the ‘chicken or egg’ question. Do authors dream it and scientists invent it? Or is it the scientific inventions that allow an author to dream? Either way, it is about how we perceive society.

How and what should our future look like? Science fiction allows unethical experimentation when looking for answers to this question. Fortunately, scientists can’t release lethal viruses and terra form planets or establish evil technocracies and post-apocalyptical governments. However, this is done in science fiction, enabling the reader to see what might happen if these things were actually done. As an instructor, sci-fi also gives me an opportunity to engage students’ intellectual curiosity and help them craft solid arguments — whether it is about analyzing technology or society.

So the next time you read science fiction or watch a sci-fi flick, ask yourself what social, political, or ecological questions are being asked and how they are answered. But remember to look at the release date because what was revolutionary in the sixties may be commonplace today.

My tips to explore strange new worlds are: Isaac Asimov’s The Franchise (1955), Tobias S. Buckell’s Resistance (2008), Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), and Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl (2009).

20,037 Total Views, 8 Views Today