This past fall, my travels and work obligations had me fly into Calgary. I took the opportunity to spend five additional days in spots I consider breathtakingly beautiful: Waterton and Glacier National Park. I crossed over the Canadian border and into Montana on a late afternoon in September and drove past herds of bison toward the village of St. Mary just as the last rays of the sun broke through the clouds and lit up the mountain ranges that rise so abruptly from the grassy plains.

For the next three nights I had booked myself into the very luxurious Lake McDonald Lodge, which is probably best known for being the proud owner of a whole fleet of vintage automobiles built by White Motor Company in the second half of the 1930s. The Lodge offers tours along the Going-to-the-Sun Road in these famous red buses. On this drive one ascends and descends numerous 180-degree serpentines along alpine passes with breathtaking vistas of mountains and waterfalls.

Because I considered these tours mere tourist traps, I at first sturdily ignored the fleet when I headed out on my daily hikes. But eventually I learned that Ford had generously renovated the famous automobiles such that they now run on gasoline and propane. Also, having driven the serpentines of Going-to-the-Sun Road by myself in thick fog upon arrival, the idea of being driven along this beautiful pass road in its glorious autumn colors began to grow on me. What I found particularly attractive was the idea of being driven around so that I wouldn’t have to turn out every other bend to avoid toppling off the mountain road because of the distractions alongside the road. And I decided that, if I ever returned, I would definitely go on such a tour. As it was, I greatly appreciated that I could now start my day hikes right from my charming room with a view of Lake McDonald.

I ventured to Mt. Brown Lookout on my first day, enjoying the beautiful autumn colors along the way and the view across Lake McDonald from the top. On the way, I met a pheasant that paraded his beautiful feathers in front of me. The next day I hiked up to Sparry Glacier and ended up above the pass in my first snowfall of the year. I also discovered plenty of bear scat on the trail up on the pass. Signs of the end of the season were everywhere: the park rangers had already dismantled the small bridges that cross the numerous waterfalls on the pass, and down at the lake the Lodge was pleasantly quiet. After three nights, I had to relocate to a small motel in St. Mary’s and fellow hikers told me that soon the water would be turned off on the campgrounds.

Although the mornings were generally quite cool and windy – some of them also rainy and misty – once the sun came out, the autumn colors glowed in all their brilliance and by lunchtime, T‑shirts were in order. My third day hike from Medicine Lake up to Cobalt Lake provided a few showers and drizzle, but I was amply rewarded with manifold beautiful rainbows along the way. Because it was moose rutting season, the moose were very active and, to my great delight, I was able to watch several of them wander about and chase deer without disturbing them or being disturbed by them. In fact, one evening an adolescent moose clattered up the path just as I parked my car next to my room.

He stopped as if to make sure I was not a rival, and so we waited and eyed each other in the dusk for several minutes before he continued on his walk across the road to some particularly inviting bush of a neighbor’s where his two wives were already busy eating. Two wives, I had been told, were a ridiculously small harem for a grown-up moose, but this one was evidently just playing at being grown up, and yet, he seemed to take himself seriously enough that I remained stock still in the shadow of my rental car.

I also hiked up Dawson Pass only to turn around out of fear of being blown off at its very top and, on my way back, got quite distracted with huckleberrying. Although there were a few hikers, I spent most days quite undisturbed and hardly met anyone on the trails except for pheasants, moose, deer, chipmunks, bighorn sheep, a pica mouse, and plenty of bear scat. I was never disappointed that I did not encounter any bears, especially since I was all on my own. While one generally starts out the day with lots of shouts and noises to make sure any potential bears are warned, I always feel that as the day wears on and the feet grow more tired, the noise-making too becomes somewhat of an effort.

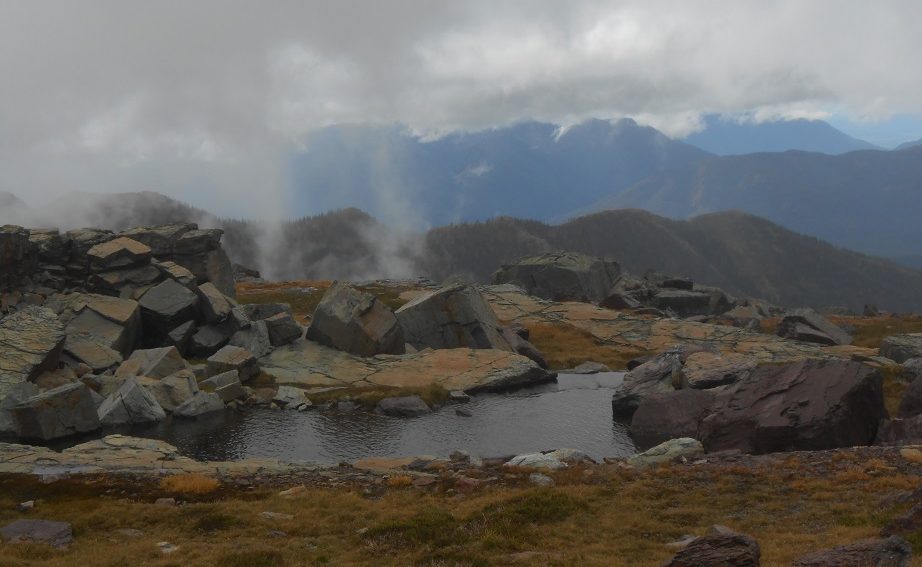

This trip was not my first into the American side of Glacier National Park. I had already been there in 2010. And as in 2010, I also travelled into Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada, after my work obligations. I had almost forgotten that I had been here six years ago, but I remembered it suddenly when I arrived at Angel Glacier one morning after some snowfall. I remembered it so well because in the course of six years a lot had changed around Angel Glacier. Not only were avalanches been keeping the park service busy, but the trail at the bottom of the glacier had been moved and the glacier itself had changed – it had shrunk significantly! In contrast to my earlier visit, I hiked up into the snowy area from where I had an even better look at Angel Glacier, whose name is derived from its former shape. By now, however, the tremendous recession of the glacier no longer resembles its former angelic shape.

The glacial recession is a phenomenon shared by all remaining glaciers in the area and also in Waterton and Glacier National Park. In fact, in the visitor center there is a miniature model of all the former 150 glaciers after whom the Glacier NP was originally named, only 25 of which are left. It is estimated that by 2030, they, too, will be gone. These anthropogenic changes were also evident as I hiked towards Grinnell Glacier, possibly one of the most trodden paths in the park. It is an easy, very accessible, and extremely beautiful hike – especially in autumn. As I trudged towards the glacier, I literally felt the changes of the Anthropocene around me, an experience that is as exciting as it is depressing and excellently documented and described by Elizabeth Kolbert in The Sixth Extinction (2014). Here she writes: “If extinction is a morbid topic, mass extinction is, well, massively so. It’s also a fascinating one. … I try to convey both sides: the excitement of what’s being learned as well as the horror of it. My hope is that readers … will come away with an appreciation of the truly extraordinary moment in which we live” (3). Such a moment can indeed be experienced in Glacier National Park: be it through the massive recession of the glaciers and the changes in the water levels, the evident movement of the terrain and the changes in the flora and fauna such as the rising tree levels, or the migration of animals in search for new habitats. On my hikes, I was as acutely aware of my own contribution to these anthropogenic changes at the same time as I witnessed and experienced them. While scientists’ and scholars’ ideas about the future of humanity in the Anthropocene diverge, I personally have mixed feelings about it. And yet, I will remember my autumnal hikes in Glacier National Park as fascinating and serendipitous moments in spite of – or because of – witnessing and experiencing the changes of the Anthropocene so vividly and directly.

18,157 Total Views, 4 Views Today