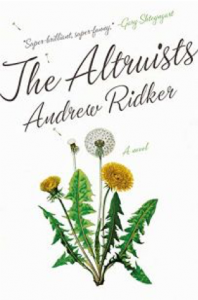

I met author Andrew Ridker at the Heine-Haus in Lüneburg on October 21, 2019. After the inspiring evening, he kindly agreed to an email interview with the American Studies Blog. His novel, The Altruists, describes a dysfunctional family burdened by their respective pasts and their attempts to repair shattered relationships. Ultimately, as the title suggests, it is also about being good.

I met author Andrew Ridker at the Heine-Haus in Lüneburg on October 21, 2019. After the inspiring evening, he kindly agreed to an email interview with the American Studies Blog. His novel, The Altruists, describes a dysfunctional family burdened by their respective pasts and their attempts to repair shattered relationships. Ultimately, as the title suggests, it is also about being good.

SV: Your debut novel, The Altruists, is reaping the highest praise from critics in the U.S. and beyond. How are you coping with all of the attention?

AR: I’m extremely grateful for the kind reviews, which have exceeded my expectations, but in my experience those highs have an expiration date of roughly twenty-four hours. After that, it’s back to work.

SV: In October, you went on a book tour in Germany (Berlin, Göttingen, and Lüneburg), Austria (Salzburg), and Switzerland (Zürich). Was it your first visit to these German-speaking countries? Did anything surprise you?

AR: I spent a week in Berlin in the winter of 2012, while studying abroad in the U.K. Other than that, I hadn’t been to any of those cities before. I was instantly enamored of the medieval architecture in towns like Göttingen and Lüneburg. On the literary side, I was struck by how long German book events tend to be – about ninety minutes – when, in the States, you can feel the audience begin to grow distracted after half an hour. I’ve also noticed, in general, that European audiences ask more abstract questions about theme and authorial intent, whereas American audiences are more interested in concrete questions of labor: How was this composed? How long did it take? What does your writing practice look like? In Europe, readers seem to view novels as irreducible works of art, whereas in the States, readers see fiction writing as a craft. Both, I think, are true.

SV: And since we are on the topic of places: I’m from Iowa and can’t resist asking you about the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. Iowa is somewhat off the beaten path for most people, but for many writers, it’s often regarded as one of the best places to study creative writing. What has it meant for your development as a writer? Is the Workshop as elitist and competitive as some have accused it to be?

AR: Iowa today is a much more nurturing place than it was in the bad old days, as I understand them, all thanks to the current director, Lan Samantha Chang. Sam has made Iowa a kinder place and a much more diverse one in terms of the student body and in terms of literary style. Nonetheless, when you drop 100 aspiring writers into a small Midwestern college town, tensions are going to rise from time to time. That tension is a byproduct of energy and ambition, which are not bad in and of themselves. I finished writing The Altruists before going to Iowa, and while I’m certain the program has had an impact on my writing, I can only guess at this point – six months after graduating – what that entails: more fluency with scene-setting and dialogue, probably. Hopefully. Most importantly, I had the time and space to write unencumbered for two years, and I made some close friends whose novels, stories, and poems will no doubt cause a stir when they hit bookstores: Sanjena Sathian, Lee Cole, Ariel Katz, Janelle Effiwatt, Sarah Mathews, and others. Remember those names!

SV: Speaking of workshopping, at Leuphana University Lüneburg, my colleagues and I teach creative writing and/or creative non-fiction. Workshopping is an important part of our program. Do you have any advice for us about how to help our students get the most out of these sessions? And do you have any advice for students who sometimes are hesitant to give or receive feedback?

AR: The workshop model, pioneered at Iowa, is imperfect, but it’s still the best I’ve seen so far. I’m in favor of the author speaking up periodically, or at the end of a workshop session, to ask questions about areas of their manuscript that might not have been addressed. The writer Tony Tulathimutte, who runs a writing workshop in Brooklyn called CRIT, recently tweeted—and I’m paraphrasing—that a workshop session isn’t quite about determining what is and isn’t working in a draft, but rather 1) articulating what the draft’s intentions are, 2) articulating what the draft is actually doing, and 3) suggesting how the draft might better achieve its aims, or in some cases proposing more interesting aims. That’s a good articulation of the question at hand. In my view, workshop submissions should not be compared against some platonic ideal of what a short story is, but rather the best possible version of itself. For students hesitant to participate, I’d say that nothing is more generous than a reader’s close attention, no matter how critical the comments are.

SV: Bernard Malamud created characters whose failures are of their own making, characters who are paralyzed by self-imposed suffering as well as characters who elicit both humor and pity. And Malamud, at least until the turbulence of the 1960s, preferred his characters’ success – however small that might be – to their failure. These characteristics seem to apply to The Altruists. Would it be fair to say that Malamud has influenced your writing?

AR: I read The Assistant at some formative age, maybe fifteen or sixteen, while on a family vacation to Italy – it’s all I remember from the trip. Take that, Bernini! I always loved the moral dimension to his work; his characters are frequently confronted with ethical dilemmas that test their best intentions. I started writing The Altruists from a more cynical place than when I finished, so in many ways I had to learn the pleasure of letting my characters succeed, however occasionally, rather than reveling too much in their failure. After all, there is much more comedy in failure than in success, but a novel in which characters do nothing but fail has failed itself to represent the vagaries of life.

SV: What about other influences on your writing? I read that you wrote your bachelor thesis on Philip Roth.

AR: Roth was big for me, as were Jonathan Franzen, Lorrie Moore, Edith Wharton, Zadie Smith, Fran Ross, Flannery O’Connor, J.M. Coetzee, Muriel Spark, I.B. Singer, Thomas Mann, Flaubert, Fitzgerald, Salinger… I seem to gravitate toward writers who cut their sorrow with irony and humor. In more recent years, I’ve been delighted to discover Karan Mahajan, Nell Zink, Keith Gessen, Ottessa Moshfegh, Jenny Offill, Rebecca Schiff, Paul Beatty, Edward St. Aubyn, and Ben Lerner as well as some older writers I had somehow overlooked, like John Cheever, Leonard Michaels, Richard Yates, Nathanael West, and José Saramago.

SV: The Altruists might be described as an experiment in character study. Would you agree? Which character or part of The Altruists did you enjoy writing most?

AR: It’s a character-driven novel to be sure. I had to write the family members’ backstories before I could push the narrative forward, which is another way of saying I had to know who I was dealing with before I tackled plot. I can’t speak to the reader’s experience, but it was certainly an experiment for me, walking that tightrope of irony and sincerity, empathy and disdain. I have to admit that I had the most fun writing Arthur, who is the novel’s id, so to speak. He thinks the unthinkable and says the unsayable. Francine, by contrast, gave me the hardest time. Her kindness, in combination with the fact of her absence throughout the book, was a challenge: how to write a complex, human character who is decent without being dull.

SV: Although all the main characters have their quirks and have made rather serious mistakes in their lives, Maggie is an especially striking character. She is a vegetarian, a zealous activist, and somewhat of a well-meaning, callous hypocrite who would rather starve herself to death and steal objects from the family home than use her inheritance to enjoy any of life’s comforts or face her demons. While she can’t really change the world, she does eventually become a driving force behind uniting her family. Where does she get the courage to do that? Is the world beyond saving?

AR: I relate a lot to Maggie. She wants to change the world but the world keeps getting in her way. And of course, she keeps getting in her own way. I think, at the novel’s end, she comes to some kind of realization that life is impossible without compromise, and that she needs to help herself and those around her before trying something more ambitious. She can’t save the planet, not on her own, at least, but she can, possibly, save her family. Whether that’s a happy ending or a sad one, depends on one’s worldview.

SV: What can you tell us about your new book project?

AR: In its present iteration, the new novel deals with the intersecting fates of three families over roughly fifteen years. Most of the characters hail from my hometown of Brookline, Massachusetts, a bastion of progressive politics and privilege, but the story will take them to England, Israel, and Germany.

SV: And finally, can you see yourself go into teaching some day?

AR: I’ve taught undergrads at the University of Iowa, and I currently teach classes in-person and online for Catapult here in New York. I love working with students. My goal is to teach in an academic setting someday; as much as I bash on the academy in The Altruists, campuses are still remarkable, almost holy, places to me.

SV: Thank you very much for your time and your insightful answers.

23,856 Total Views, 12 Views Today