was late in June 2015. I was on a trip through the southern United States and decided to take a quick detour to explore the area around South Carolina’s statehouse in the city of Columbia. Here, only a few days earlier, Brittany (“Bree”) Newsome, had scaled a 30-foot flagpole to take down the Confederate flag, an act that had captured national and international media headlines. This incident was one of several notable recent flashpoints in the culture wars that rage over issues of historic commemoration.

was late in June 2015. I was on a trip through the southern United States and decided to take a quick detour to explore the area around South Carolina’s statehouse in the city of Columbia. Here, only a few days earlier, Brittany (“Bree”) Newsome, had scaled a 30-foot flagpole to take down the Confederate flag, an act that had captured national and international media headlines. This incident was one of several notable recent flashpoints in the culture wars that rage over issues of historic commemoration.

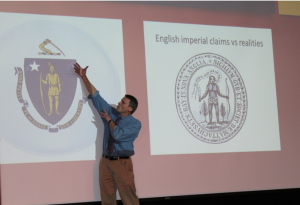

There was a certain irony in my visit that did not escape me since I was travelling through South Carolina to get to Savannah, Georgia, for a conference where I was going to speak on another controversial flag – the 17th century Seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This seal serves as the precursor of the current flag of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Students and public audiences are usually surprised and sometimes shocked when confronted with an image of the Seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It depicts a scantily dressed Native American, covered with only a few leaves. The image also features a speech bubble stating: “Come over and Help Us.”

The current Massachusetts flag is based on the original Massachusetts Bay Colony Seal. It is more familiar to students and public audiences and, at first glance, may seem more appropriate. The Native American depicted in today’s flag is clothed and the speech bubble has disappeared.

Yet the flag, created in the late 19th century, has several disturbing features. The body of the indigenous person in the image was modeled after a Native American skeleton found in Winthrop, Massachusetts. The face, however, is based on that of a 19th century Native American from Montana. Despite the continuous presence of indigenous peoples in the region, white New Englanders, by the 19th century, had either come to believe that Native Americans had disappeared from the Northeast or maintained that those who remained were not “Indian” enough anymore.

Another curious choice in the depictions is the sword hanging over the head of the indigenous person. This sword is based on Miles Standish’s weapon. Standish served as the military advisor to the Puritans on the Mayflower and afterwards as the commander of Plymouth colony. Under his leadership, during the first violent encounter with the Massachusetts, several Native Americans were killed, and one fighter’s head was cut off and displayed outside of Plymouth. The severing and piking of heads was not a one-time occurrence during the Puritan colonization of New England. It was a destiny shared by several Native leaders, such as Metacomet, known to the English as King Philip, who led a militant resistance movement against the New English colonies in the 1670s. Metacomet’s belt was used as the model for the one on the flag, and his head was displayed outside of Plymouth for two decades after his killing. Such historic incidents make the placement of the sword above the head particularly cringe worthy. Moreover, the motto inscribed on the flag reads in Latin: “By the sword we seek peace.”

While the flag of Massachusetts receives little national or international attention, it nonetheless raises important questions about the representation of Native Americans that emerges out of complicated histories of colonization, race, representations, and memory. Both the historic seal and the contemporary flag provide an interesting case study of the historic representation of Native Americans and the continuous impact those have on contemporary society. As we are commemorating the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower, these issues of representation deserve wider public awareness, consideration, and informed civil discussion. See for yourself how the movement to change the Massachusetts State Flag and Seal continues.

25,798 Total Views, 9 Views Today