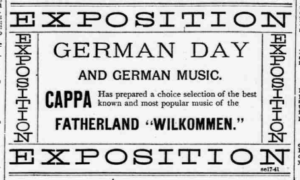

It is one of the founding myths of “German Americana” that the first migrants from German-speaking territories arrived on October 6, 1683, on North American soil. Unsurprisingly, German Americans have always sought to celebrate this particular date in order to promote and to secure German American traditions and interests. Such celebrations, formerly often called “German Day,” flourished during the 19th century and ceased after the world wars. After the 1983 tricentennial, German American stakeholders were able to revive and to continue the celebrations: On August 18, 1987, Congress approved a joint resolution to designate October 6, 1987, as German-American Day.

Since that time, most American presidents have issued annual proclamations to celebrate the achievements and contributions of German Americans to our Nation with appropriate ceremonies, activities, and programs. Also, German American societies have taken on the ‘task’ and included annual German-American Day celebrations into their calendars, often in combination with the famous Oktoberfest.

When teaching German American Day in high school and university classes, faculty of all levels need not yield to temptation: They can’t just simply celebrate a somewhat blurred German American identity with their students, but should allow for a critical assessment of German American history. Here are three ideas to get started:

Most presidential proclamations emphasize the “arrival of the first German settlers” on October 6, 1683, call upon “all Americans” to celebrate German American “achievements and contributions” to American history, and tend to showcase certain aspects of German American impact on the “national landscape.”

- Have your students research who these first settlers were and whether it is appropriate to label them as German settlers.

To begin with, your students may read the 1983 New York Times article, “Obscure German Pilgrims Star in a Tricentennial.” Take this article as a starting point to discuss ascriptions of nationality, ethnicity, and race. Explore the history of these people, often described as “Krefelders,” and learn more about their relation to William Penn, Native Americans, and African Americans. In addition, consider the concepts of settler colonialism and settler imperialism.

- Have your students discuss German American contributions to American history.

It is a master narrative of American history that German-speaking migrants were industrious laborers who contributed to the making of America more than any other group. This narrative, of course, silences the contributions of many people whose achievements are often forgotten, less emphasized, or put into an overly simplified context. For instance, early German-speaking migrants in colonial Louisiana are often credited with saving the colony from starvation. In this context, it is rarely mentioned that these migrants heavily relied on slave labor. Find similar examples with your students.

- Have your students take a closer look at German American ‘success stories’.

While some migrants thrived on the American continent, many struggled, and others even returned home. The “German-American Immigrant Entrepreneurship” project of the German Historical Institute, Washington, D.C., gives examples of many successful migrants. To learn more about the everyday experience of migrant life in the United States, you will have to dig into immigrant letter collections. Luckily, many of these collections are now available digitally. The “German Heritage in Letters” database, for instance, offers a fine collection of original letters transcribed and translated into German and English.

Last but not least, you may now try to find out which remnants of German American life – apart from the folkloric – have actually survived into the 21st century.

After completing these tasks, my hope is that you’ll have a much deeper understanding of German American history. And if these ideas come too late for this year’s German American Day, there is always the next.