It was in the late afternoon on November 22, 2018. Even by New England standards, the weather was cold and blustery. Outside of a dormitory at the university where I teach, I met up with a German student who spent the 2018 fall semester as a Fulbright exchange student at my institution. My family had him over for dinner before, and, as he had no place to go for Thanksgiving, we invited him to spend the holiday dinner at our house along with a few other friends. When I picked him up, he was clearly surprised as the dormitory and the university appeared completely abandoned. I explained to him that Thanksgiving was ‘the’ big family event in the United States and that extended families are more likely to get together during this holiday than for Christmas or the Fourth of July.

The dinner table – resplendent with a large roasted turkey, mash potatoes, various breads and greens, as well as sweet potato and cranberry dishes – reminded me of my first Thanksgivings in 1993. I had just arrived in the U.S. and was looking forward to my job as a German language assistant at a small liberal arts college. Since those days, I have often wondered about the various meanings that Americans ascribe to the holiday and the sometimes ambiguous and even contested relationship that many have with Thanksgiving. As a historian, I am fascinated by how the history that surrounds the holiday is often ignored or sanitized by many in mainstream American society. In fact, Native Americans tend to have an entirely different perspective on Thanksgiving, but more about that later.

The Thanksgiving holiday is not only a time to meet family and friends; it is also connected to the foundational myth of New England and the United States: the Mayflower and the establishment of Plymouth Colony late in 1620. The celebratory meal that many families all over the United States hold, commemorates a feast of giving thanks for the abundant harvest the Plymouth colonists enjoyed in the fall of 1621. The celebration included English colonists and Native Americans who had taught the English how to farm and survive in the new land. The tradition of the meal continued among some New English families and spread beyond the region. It was Abraham Lincoln who turned Thanksgiving into a public national holiday during the Civil War era, and it gradually became part of the country’s historic memory and civil religion. In many pre-and primary schools throughout New England and the United States, children still dress up as ‘Pilgrims’ and sometimes as ‘Indians’ to this day around Thanksgiving,

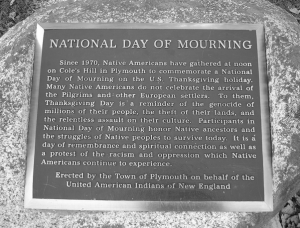

Since 1970, Native Americans from New England and beyond gather for a National Day of Mourning on Thanksgiving Day in Plymouth, Massachusetts, commemorating a different version of these past events. Every year, Native Americans march through town and gather on a hill overlooking Plymouth Rock, a memorial built at the place where the Puritan colonists supposedly once landed. Here speeches and musical performances commemorate and protest Native American loss of life and land as a result of the long, destructive, and painful history of colonization. Indigenous activists have also installed a plaque on the hilltop that reminds the public of “the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture.” Yet, the speeches also emphasize indigenous survival in New England and beyond. Speakers address the challenges faced by modern Native American societies, such as alcohol and drug addiction, crime rates, sexual violence, and language retention. To Native American activists, the ceremony serves as a reminder that Native people in New England have not been conquered and disappeared, but are still here.

22,265 Total Views, 10 Views Today