By Christoph Strobel

It was in the late afternoon on November 22, 2018. Even by New England standards, the weather was cold and blustery. Outside of a dormitory at the university where I teach, I met up with a German student who spent the 2018 fall semester as a Fulbright exchange student at my institution. My family had him over for dinner before, and, as he had no place to go for Thanksgiving, we invited him to spend the holiday dinner at our house along with a few other friends. When I picked him up, he was clearly surprised as the dormitory and the university appeared completely abandoned. I explained to him that Thanksgiving was ‘the’ big family event in the United States and that extended families are more likely to get together during this holiday than for Christmas or the Fourth of July.

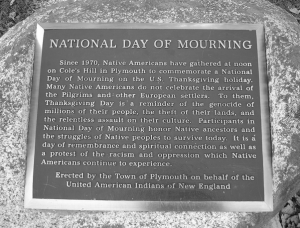

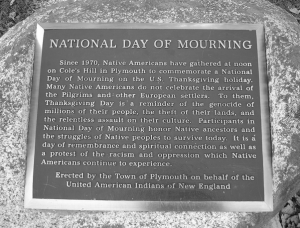

The dinner table – resplendent with a large roasted turkey, mash potatoes, various breads and greens, as well as sweet potato and cranberry dishes – reminded me of my first Thanksgivings in 1993. I had just arrived in the U.S. and was looking forward to my job as a German language assistant at a small liberal arts college. Since those days, I have often wondered about the various meanings that Americans ascribe to the holiday and the sometimes ambiguous and even contested relationship that many have with Thanksgiving. As a historian, I am fascinated by how the history that surrounds the holiday is often ignored or sanitized by many in mainstream American society. In fact, Native Americans tend to have an entirely different perspective on Thanksgiving, but more about that later.

Read more »