In order to celebrate Cinco de Mayo, the – unfortunately not official – holiday of Mexican Americans in the United States, I’d like you to do the quiz and see how much you know about “la cultura chicana.”

In order to celebrate Cinco de Mayo, the – unfortunately not official – holiday of Mexican Americans in the United States, I’d like you to do the quiz and see how much you know about “la cultura chicana.”

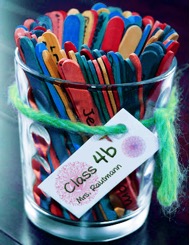

Imagine the following situation: You want your students to read out their results, but you are running low on time. Your students are highly motivated, and most of them want to share their work with the class, but it is clear from the start that you can’t involve all of them. What do you do now? Pick your ‘favorite’ child? Pick the child who did the best job as an excellent example to the rest of the class? Or would it be better to involve the shy child and give her a chance to contribute to the class? Will some children feel neglected or preferred?

Last summer, I spent three months in the United States where I’d been offered a chance to observe different elementary school classes. There I found a solution to the problem mentioned above. In one class – full of highly motivated fourth graders – I noticed a beautifully decorated jar filled with tongue depressors. At first, I couldn’t think of any purpose for this glass, so I decided to ask the teacher about it after class.

Last summer, I spent three months in the United States where I’d been offered a chance to observe different elementary school classes. There I found a solution to the problem mentioned above. In one class – full of highly motivated fourth graders – I noticed a beautifully decorated jar filled with tongue depressors. At first, I couldn’t think of any purpose for this glass, so I decided to ask the teacher about it after class.

We’re very happy to present this tremendous collection of articles, edited by Ingrid Gessner and Uwe Küchler: http://www.asjournal.org/70–2020/

Project seminars are always challenging. Since they involve more work than a traditional seminar, they often attract those types of students who enjoy a good challenge and want to create something lasting. During the summer semester 2020, it was no different. Well, at least during the planning phase. But then Covid-19 hit. Within three weeks, we had to transform our seminar to remote learning. There was much to learn, and the ecocritical project I had envisioned took a major detour into the unknown. Originally, I had planned – as I had done in past semesters – to have students create different projects on campus or in and around Lüneburg, for example guerilla gardening or various installations (for which we often needed the university’s permission). However, during a lock down in which we were only supposed to leave our homes to go to work, the doctor, or the supermarket, I quickly knew that tried-and-true recipes for a successful project seminar would not work. So what could we do?

Well, it wasn’t long after explaining the predicament to my students that they came up with an idea. And a great idea it was.

We’re very happy to present this tremendous collection of articles, edited by Heike Paul, Martina Kohl, & Hans-Jürgen Grabbe: asjournal.org/69–2020/

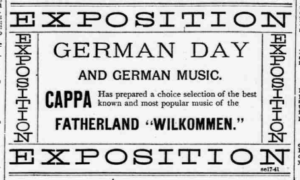

It is one of the founding myths of “German Americana” that the first migrants from German-speaking territories arrived on October 6, 1683, on North American soil. Unsurprisingly, German Americans have always sought to celebrate this particular date in order to promote and to secure German American traditions and interests. Such celebrations, formerly often called “German Day,” flourished during the 19th century and ceased after the world wars. After the 1983 tricentennial, German American stakeholders were able to revive and to continue the celebrations: On August 18, 1987, Congress approved a joint resolution to designate October 6, 1987, as German-American Day.

Since that time, most American presidents have issued annual proclamations to celebrate the achievements and contributions of German Americans to our Nation with appropriate ceremonies, activities, and programs. Also, German American societies have taken on the ‘task’ and included annual German-American Day celebrations into their calendars, often in combination with the famous Oktoberfest.